Connect with the Libraries

Have an idea for Subject of the Month?

February 2021 Black History Month

February is the month dedicated annually to Black History. This February, the University Libraries have partnered with the WSU Office of Multicultural Student Engagement (OMSE) to develop this virtual Subject of the Month display spotlighting people and events of historical influence in the African American community in Detroit. We hope you will enjoy exploring and learning about black history in our great city.

The virtual display was conceived by Joseph Bradfield, Student Engagement and Retention Coordinator, and designed by Dajah Callen, Social Media and Marketing Assistant, Office of Multicultural Student Engagement (OMSE), along with Veronica Bielat, Subject Specialist Librarian, University Libraries.

On February 8, Wayne State Special Collections will launch "Courage Without Compromise: An Exhibition," a virtual exhibition highlighting civil rights and social justice material from the African American Literature Special Collection, the Arthur L. Johnson Collection, and the Collection of African American Legal History. To learn more, and to view the exhibition, on Feb. 8, visit tinyurl.com/CourageWithoutCompromise.

Dr. Ossian Sweet (1895-1960)

Dr. Ossian Sweet was a Physician. After completing his medical degree at Howard University, Sweet moved to Detroit, Michigan in the late summer of 1921. Sweet later became affiliated with Dunbar Hospital, Detroit's first hospital founded to serve the black community. In 1925, Sweet purchased a house at 2905 Garland Street, in an all-white neighborhood, with the hopes of establishing a medical practice in his home. His decision to move outside of Black Bottom, one of the few places in the City that allowed African Americans to purchase property, changed this man and his family’s future drastically, while also causing the creation of Michigan Firearm Registration Laws.

Ossian Sweet and his wife, Gladys, purchased this house in May 1925, located at 2905 Garland Street. When the Sweets moved into their home on September 8, white residents who objected to blacks moving into the neighborhood formed a crowd on the street. The next day hundreds of people converged on the corner of Charlevoix and Garland Streets intent on driving the Sweets from their home. The mob threw rocks and bricks at the house while the Sweets and nine others took refuge inside. In the evening shots rang out and a white man was killed. The police charged the people inside the Sweet house with murder. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People hired attorney Clarence Darrow, who argued that people, regardless of their race have the right to protect their homes.

Photo from michmarkers.com Michigan Historical Markers Web Site http://www.michmarkers.com/default?page=S0461

-

Arc of Justice by

ISBN: 0805079335Publication Date: 2005-05-01"Historian Kevin Boyle weaves the police investigation and courtroom drama of Sweet's murder trial into an unforgettable tapestry of narrative history that documents the volatile America of the 1920s and movingly re-creates the Sweet family's journey from slavery through the Great Migration to the middle class. Ossian Sweet's story, so richly and poignantly captured here, is an epic tale of one man trapped by the battles of his era's changing times.”

Dr. Rosa L. Gragg (1904-1989) Detroit Association of Colored Women's Club

Rosa Gragg was a major Civil Rights and Women’s Rights activist and consultant to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an associate of Mary McLeod Bethune, and served as an advisor to three U.S. Presidents: Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Lindon B. Johnson. It was because of her efforts, that African Americans were able to begin to purchase and own properties in the City of Detroit, outside of the Black Bottom area.

Gragg’s career in activism began in the 1930s; she frequently gave speeches about how to improve race relations in the United States. Then, in the 1940s, Gragg began to get involved in politics. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her to a national advisory board, the Board of the National Volunteer’s Participation Committee of Civil Defense.

Gragg’s activism also called for education reform. In 1947, she founded the Slade-Gragg Academy of Practical Arts in Detroit because she believed that education was crucial in the struggle for black progress. The academy was the first black-owned and operated business on Woodward Avenue. It offered classes in trades including tailoring, dress-making, and food service and preparation.

Image Source: Detroit Public Library Digital Collections

Lifting as We Climb

Detroit Association of Colored Women's Clubs was organized on April 8, 1921, with eight clubs. This association reached its peak membership in 1945 with 73 clubs and 3,000 members. Affiliated with the Michigan and National Associations of Colored Women's Clubs, the Detroit association fosters educational, philanthropic, and social programs. The association was incorporated in 1941. That same year, supported by a mortgage on its president's home, the association purchased the present clubhouse located at the corner of Ferry and Brush Streets, a handsome Colonial Revival style structure. The club members completely paid for the clubhouse in less than five years. The association sponsors girls' clubs, scholarships, annual clothing drives for needy school children, and charitable programs for seniors and the dispossessed.

In 1958, Gragg was elected president of the national organization. Her accomplishments in this role were impressive. In 1961, she launched a restoration campaign for the Frederick Douglass house, and the following year, Senate Bill 2399 declared the home a historic site. In thanks, Gragg gifted an Abraham Lincoln portrait from Frederick Douglass’ library to the White House. This marked the first time in United States history that a black organization gave a gift to the White House.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/places/detroit-association-of-colored-women-s-clubs.htm

Dr. Gragg's work lives on with what is now called the Detroit Association of Women's Clubs in the same home she purchased for the organization so many decades ago."She was there when the significant things impacted our community, the black community," says current Women's Clubs president Angela Calloway. "She was there when the Voting Rights Act was signed. She was there when the Civil Rights Act was signed." Dr. Rosa L. Gragg passed away in February of 1989. A portion of Ferry Street was renamed Dr. Rosa L. Gragg Blvd in 2019 as a tribute to the contribution she made to her community. Calloway is doing her part to keep Dr. Bragg's memory alive.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) "I Have A Dream" Detroit Speech

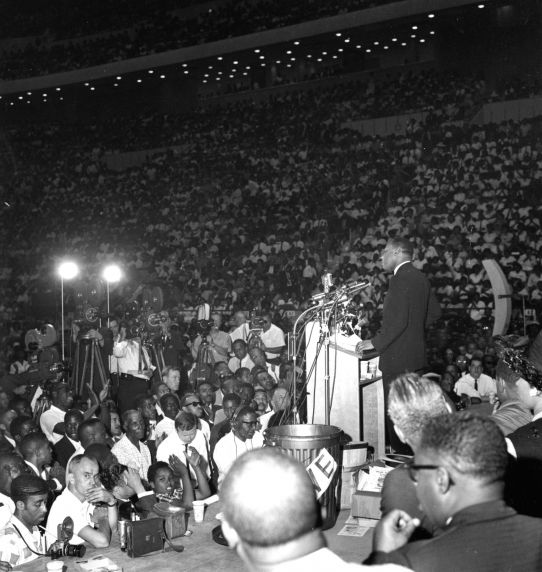

Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at Cobo Hall (now TCF Center) in June 1963

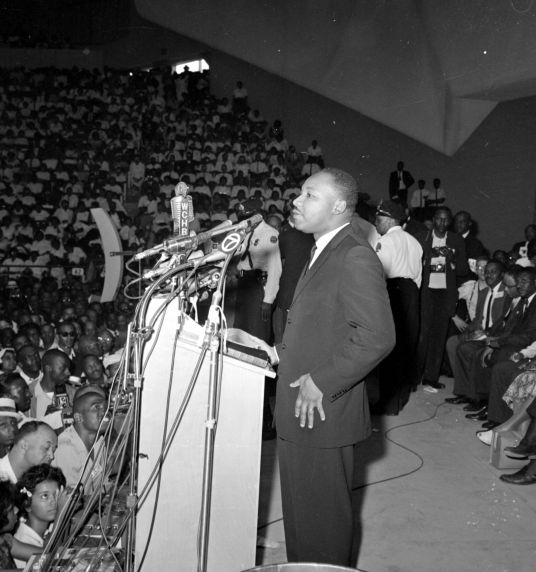

In June 1963, a crowd of 125,000 took to the streets of Detroit in the Walk to Freedom march that eventually concluded at Cobo Hall (now TCF Center). While at Cobo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a rousing 30-minute speech — an early take on what would become his famous "I Have A Dream" speech in Washington D.C. for the March on Civil Rights weeks later.

Martin Luther King Jr.- I Have A Dream- Detroit Speech Cobo Hall (now TCF Center)

Two months before his famous speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led marchers down Woodward Ave. in Detroit. Rev. King famously called the March “the largest and greatest demonstration for freedom ever held in the United States.”Over 125,000 people participated in the “Detroit Walk to Freedom” on June 23, 1963. The March was partially a practice run for the historic “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.”

Photograph from the Reuther Library

Martin Luther King Jr.- I Have A Dream- Detroit Speech Cobo Hall (now TCF Center)

The event was organized by the Detroit Council for Human Rights, a group formed of religious leaders and activists, who conceived of the march in order to raise funds and awareness for their civil rights contemporaries in the South, as well as to protest the issue of segregation in the North. The date of June 23rd was chosen to honor the 20th anniversary of the Detroit race riot of 1943. A crowd of approximately 100,000 marched down Woodward Ave from Adelaide St to Cobo Hall (now TCF Center).

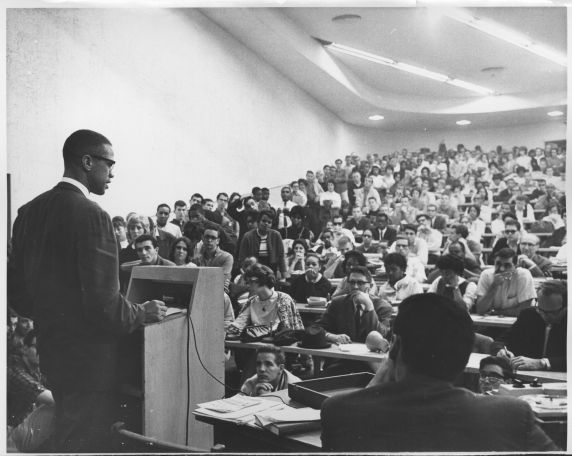

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz (Malcolm X) (1925-1965) Visit to WSU

Students pack into Wayne State University's 101 State Hall to hear a lecture by Malcolm X.

In 1963, the Independent Socialist Club of Wayne State University sponsored a lecture by Malcolm X in 101 State Hall, with over 400 students in attendance. The focus of the lecture was on the aims of the Nation of Islam. A warning regarding future race wars was also given: "We are not afraid to go to jail or afraid to take the life of those who take our life. We believe the fair exchange. This is the price of freedom, and we are prepared to pay the price."

-

The Autobiography of Malcolm X (as told to Alex Haley) by

Call Number: BP 223 .Z8 L57943 1965b (Undergraduate Library)ISBN: 0345350685Publication Date: 1987In this classic autobiography, originally published in 1964, Malcolm X tells the extraordinary story of his life and the growth of the Black Muslim movement. -

Malcolm X's Michigan Worldview by

Call Number: ebookISBN: 9781609174507Publication Date: 2015Malcolm X's Michigan Worldview presentas Malcolm's subject as an iconography used to deepen understanding of African descendent peoples' experiences through advanced research and disciplinary study. The book presents Malcolm as a Black subject who represents, symbolizes, and associates meaning with the Black/Africana studies discipline.

Dr. Charles Wright (1918-2002) Medical Doctor and Cultural Leader

Charles Howard Wright was an accomplished Detroit physician and founder of the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. Born in Dothan, Alabama on September 20, 1918, Wright attended Alabama State College, obtained his M.D. from Meharry Medical School in 1943, and served an internship at Harlem Hospital in New York. Charles Wright was married to Louise Lovett, with whom he had two children. Following Lovett’s death, he married Roberta Hughes in 1989. Dr. Wright died on March 7, 2002 and is buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Dr. Wright practiced general medicine in Detroit for four years, starting in 1946. He went back to Harlem for a residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology before returning to Detroit in 1955 where he was certified as an OB-GYN specialist and general surgeon. He became an emeritus attending at Harper-Grace Hospital, and a senior attending physician at Sinai Hospital. Wright also worked at Wayne State University Medical School from 1969-1983 as an assistant clinical professor. He later became a senior attending physician at Hutzel Hospital, eventually retiring in 1986. Wright was active in social issues and was a lifelong member of the NAACP. He started the African Medical Education Fund through the Detroit Medical Society and served as a physician during civil rights marches in Louisiana in 1965.

Dr. Wright’s most notable achievement in the City of Detroit was founding the Museum of African American History. It began as the International Afro-American Museum, located in part of his office on West Grand Boulevard. Feeling the need for a museum to commemorate, preserve and promote the history of African Americans, Dr. Wright led a partnership of 30 people in 1965 to establish the museum. Wright’s new museum included African masks from Nigeria and Ghana and information on notable African American Detroiters.

In 1978, the City of Detroit provided land for a museum in Midtown and funds were raised for a new building that opened in 1987 at 301 Frederick Street. The name was changed to the Museum of African American History. When the museum outgrew that facility, Detroit voters approved a bond for a third building at 315 E. Warren in the University Cultural Center, which opened in 1997 - the largest African American history museum in the world. A year later it was renamed the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in honor of Dr. Wright.

Image Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/26/Charles_Wright_African-American_Museum.jpg

Dr. Horace Bradfield (1913-1993) WSU Medical School Graduate

Horace Bradfield was born in Denver, Colorado in 1913. His family moved to Detroit in 1919. He was a Physician/Gynecologist at Providence and Hutzel hospitals and a Board of Trustee of Wayne County Community College. He attended the College of the City of Detroit, one of the schools that would be merged to later become Wayne State University. He transferred to the University of Michigan and graduated with a Bachelor and Master of Science (both in Chemistry) in 1934 and 1935, respectively. He graduated from Wayne State University in 1948 as a Doctor of Medicine.

Bradfield became the fifth Black intern at Detroit Receiving Hospital before coming to Providence and Hutzel hospitals in Detroit to work as a physician. He delivered thousands of babies and treated thousands of patients at his office located at 3006-3008 East Grand Boulevard in Detroit 48202, the Detroit's North End Neighborhood. He retired from medicine in 1989. He was a community leader with a lifelong commitment to helping poor people. Bradfield served on the board of Wayne County Community College, and the board of directors for the Detroit Urban League in the 1960s-1970s.

Source: Bentley Historical Library

Marjorie A. Blackistone and Horace Ferguson Bradfield papers

The Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan holds the Marjorie and Horace Bradfield collection, which contains Marjorie Bradfield's autobiography, audio recordings of interviews with Horace Bradfield, and photographs of the Bradfields.

You can listen to a recording of a 1978 interview with Dr. Horace Bradfield, facilitated by his daughter, Trudy Bradfield Taliaferro.

-

Untold Tales, Unsung Heroes: an oral history of Detroit's African American community, 1918-1967 by

Call Number: ebookISBN: 9780814324653Publication Date: 1993More than one hundred individuals who lived in Detroit share stories about everyday life--families and neighborhoods, community and religious life, school and work.

Horace Bradfield is noted in the acknowledgments as contributing to the publication of this book.

Ken Cockrel Sr. (1938-1989) Detroit City Councilman

Ken Cockrel- Politician

Kenneth Cockrel Sr. was an American politician, prominent attorney, and revolutionary, community organizer, from the city of Detroit. Cockrel served as a member of Detroit's Common Council, from his swearing-in in 1978 until 1982. In addition to winning major cases representing poor and working class Detroiters, Cockrel rose to political prominence as he helped organize social and political movements, including the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and other radical black, Marxist formations.

Image source: Reuther Library

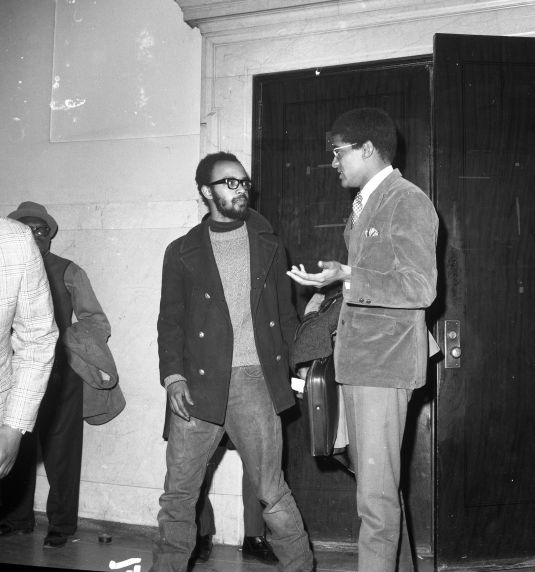

John Watson, editor of the South End student newspaper, speaks with Kenneth Cockrel

Before joining the City Council, Cockrel worked as a reporter for the Detroit Free Press, the Grand Rapids Press and the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Image Source: Reuther Library

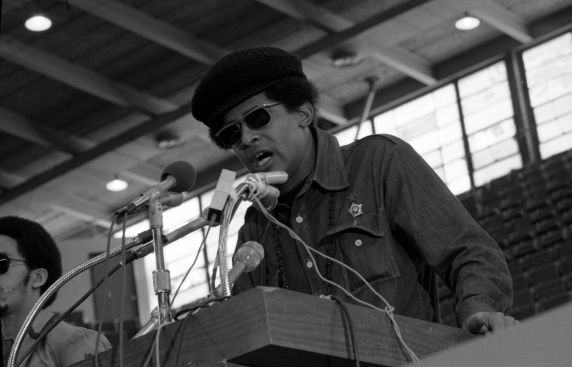

Attorney Kenneth Cockrel addresses the audience at an Anti-STRESS (Stop the Robberies and Enjoy Safe Streets) event in Detroit, Michigan.

Cockrel has worked on numerous issues during his time in office. He is dedicated to improving city neighborhoods and to expand drug-free zones around schools and parks. Every year Cockrel gives out more than 500 turkeys to needy families and senior citizens through his Annual Thanksgiving Turkey Giveaway.

Image Source: Reuther Library

Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Papers at the WSU Walter P. Reuther Library

The Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection consists of correspondence, reports, government surveillance files, minutes, newspaper clippings and other media coverage, speeches, articles and radio commentaries, legal case records and other material documenting the Cockrels' involvement in progressive social and political causes in Detroit in the 1960's and 1970's as well as Mr. Cockrel's activities as a Detroit City Councilman.

For more information on this collection, contact the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University.

Image Source: Wayne State University Virtual Motor City Digital Collections, Walter P. Reuther Library.

APREL Teaching Resources

APREL (Archives & Primary Resource Education Lab) provide document sets and teaching resources to support educators integrating primary resources into their teaching.

Ken Cockrel was a leader in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. This lesson is designed to introduce students to the history of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers through close examination of a set of archival documents. The purpose of these assignments is to give students the opportunity to interpret history from first-hand accounts of materials produced by League members themselves. Secondary reading is available at the end of each lesson to provide historical context; however, the focus throughout should remain on the primary source materials. It is with those sources that students will be able to form original questions and think critically about the specific conditions that gave rise to the LRBW. Students will come away with a clear understanding of why the LRBW emerged, its specific grievances and the tactics used by members to advance their cause. It is important to keep in mind that members of the League – like all historical actors – can be best understood when situated within a particular time and place.

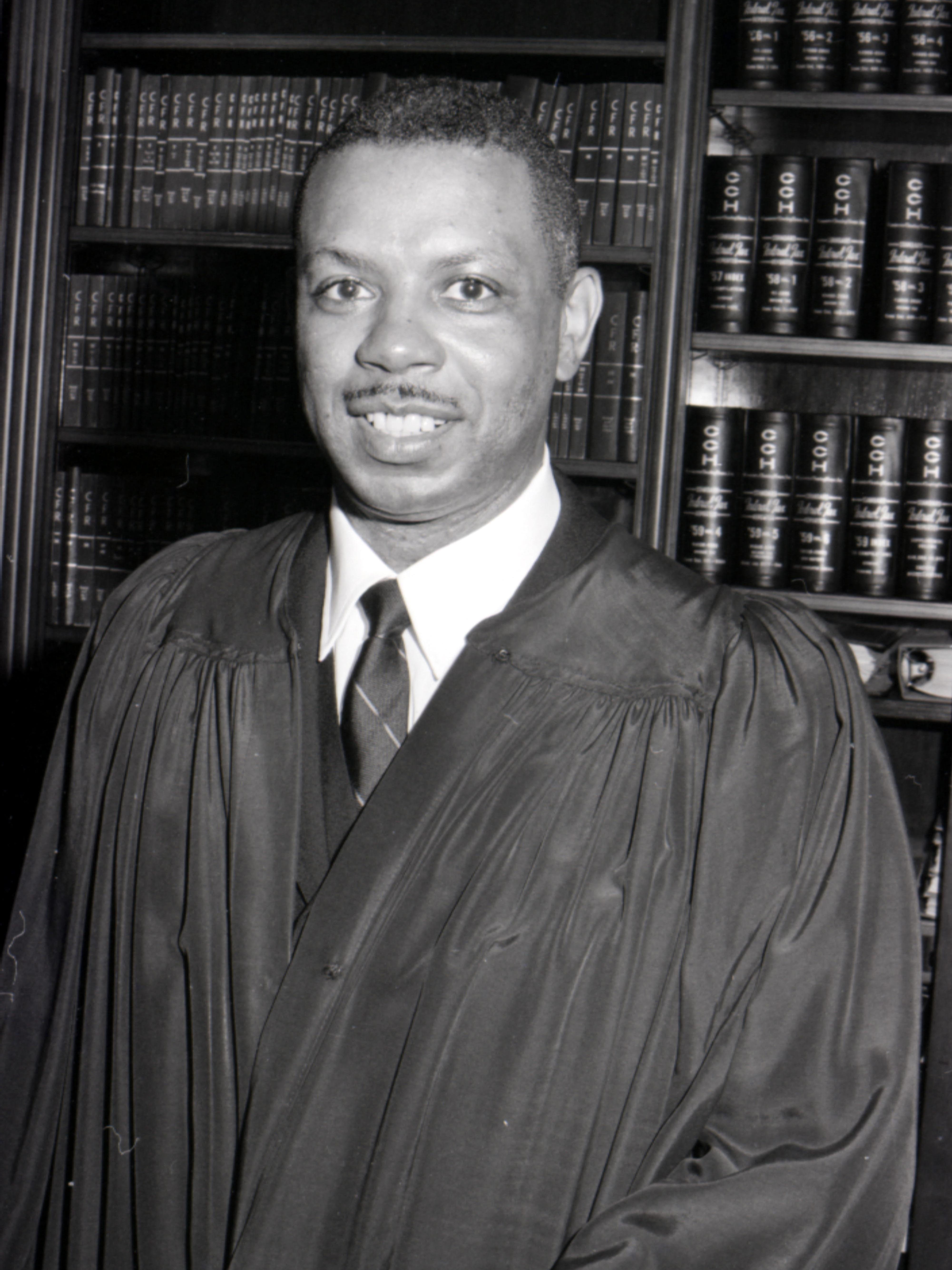

The Honorable Damon Keith (1922-2019) Judge of the US Court of Appeals

Damon J. Keith was a U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals judge whose rulings as a federal district judge in Detroit in the 1970s catapulted him to the status of civil rights icon, died peacefully in his sleep early Sunday at his riverfront apartment in Detroit. He was 96.

Keith, the grandson of slaves and the longest-serving African-American judge in the nation, burst onto the national stage in 1970 when, as a U.S. district judge, he ordered citywide busing to desegregate Pontiac schools. It was the first court decision to extend federal court-ordered busing to the North.

Keith graduated from Northwestern High School in 1939. He later enrolled at West Virginia State College, an all-black school in Morgantown. He worked his way through college by cleaning the chapel and waiting tables in a dining hall. After college, Keith was drafted into the segregated U.S. Army and spent three years driving a truck in the Quartermaster Corps during World War II in Europe. He was discharged as a sergeant in 1946.

He attended Howard University, a historically black Washington, D.C., college, eventually receiving his Bachelor's of Law. After getting his law degree in 1949, Keith worked as a janitor at the Detroit News while studying for his bar exam. He twice failed the bar exam but received his law license after appealing the second score. In 1952, he became the first black lawyer for the Wayne County Friend of the Court. Four years later, he returned to his old law firm, this time as a lawyer, and obtained a Masters in Law in 1956 from Wayne State University.

In 1964, he opened his own law firm, which eventually became known as Keith, Conyers, Anderson, Brown & Wahls. The firm moved into the Guardian Building, becoming the first black law firm in the city’s all-white legal district. The firm represented several prominent black businesses and other clients, including future Detroit Tigers’ great Willie Horton.

Keith was especially proud of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights, which opened at Wayne State University in 2011. The $5.7-million addition to the WSU Law School chronicles Keith’s judicial career, the legal history of the civil rights movement and the accomplishments of African-American lawyers and judges.

-

Judge Damon Keith: A Life of Service and Great PurposeAPREL (Archives & Primary Resource Education Lab) provide document sets and teaching resources to support educators integrating primary resources into their teaching.

This document set will provide students with an opportunity to explore and examine some of Judge Damon Keith's work, from his ruling to integrate Pontiac Schools in the 1970's to the opening of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University in 2011. Students will also be able to reflect on what they may want to contribute to society within their own lifetime.

This resource includes:

1. A teacher plan to support classroom use of materials

2. A document gallery including just the primary sources

3. Additional resources such as books and documentaries that can be used in class or as homework

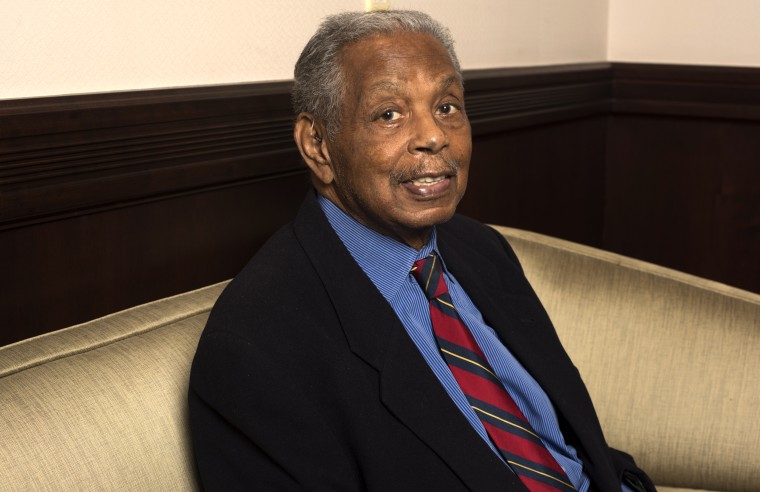

Dr. Arthur Jefferson (1937- ) First African American Superintendent of DPS

Arthur Jefferson, Superintendent of Detroit Public Schools.

Dr. Arthur Jefferson possessed earned B.A., M.A., and Ed.D degree from Wayne State University. He was appointed Interim Superintendent of Detroit Public Schools in June 1975 with the Interim removed by the end of that year. Jefferson was the first African American Superintendent of Detroit Public Schools. Jefferson was the Chairman of the Board when the African American Museum was opened in Detroit in 1965. He served on the Advisory Committee to national Review panel on School Desegregation Research, 1977-79.

Arthur Jefferson's Doctoral Dissertation

Arthur Jefferson received his Doctorate of Education in 1973. Read his dissertation "Descriptive and Evaluative Analysis of Selected Services Provided by a Detroit Public School Region".

Image Source: Detroit Historical Society

https://s3.amazonaws.com/pastperfectonline/images/museum_428/209/thumbs/2014114613.jpg

Locations of the People and Places Highlighted on this Guide

Black Bottom and Paradise Valley

-

Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, What Happened? Two Lost African American Communities, How Can History be Restored?Ken Coleman, 10/5/2017, Detroitisit

-

The Bottom: The Emergence and Erasure of Black American Urban LandscapesUjijji Davis, Avery Review 34 (October 2018).

Horace Stephen Ferguson (1870-1945) Black Bottom Restaurant Owner

Horace Ferguson

Horace Ferguson was born in Lebanon, Ohio in 1870. He came to Detroit from St. Louis, Missouri in 1916, and opened the first of a series of restaurants in the Black Bottom area of Detroit. He was well known for his philanthropy and community activity. Ferguson died in 1945, and in his obituary, it was noted that "No man ever entered his restaurants and left without a meal, regardless of whether he had the price or not." (Michigan Chronicle)

A look inside No Tipping Lunch

This is an image inside one of Ferguson's restaurants.

Horace Stephen Ferguson's Restaurants

Horace Stephen Ferguson was the sole owner of 4 restaurants in the city of Detroit, commonly known as St. Louis Lunch, 1721-1723 St. Antoine street, No Tipping Lunch, 1721-1723 St. Antoine street, No Tipping Lunch, 4868 Beaubien street, Evergreen Lunch, 2641 Hastings street, and Housewife's Lunch, 5700 John R. street.

Ferguson employed, paid, and discharged the help, paid the rent, telephone, gas bills, et cetera, and took leases in his own name on the premises occupied by the restaurants, and that no one asserted any authority over his activities or gave him any orders in or about these establishments.

Black Bottom and Paradise Valley: Center of black life in Detroit

In 1942, the Detroit Urban League reported that within Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were:

| 151 physicians | 30 drug stores | 10 electricians |

| 140 social workers | 25 barber shops | 9 insurance companies |

| 85 lawyers | 25 dress makers and shops | 7 building contractors |

| 71 beauty shops | 20 hotels | 5 flowers shops |

| 57 restaurants | 15 fish and poultry markets | 2 bondsmen |

| 36 dentists | 10 hospitals | 2 dairy distributors |

Frederick Douglass meeting with John Brown in Detroit

Meeting Place, home of William Webb

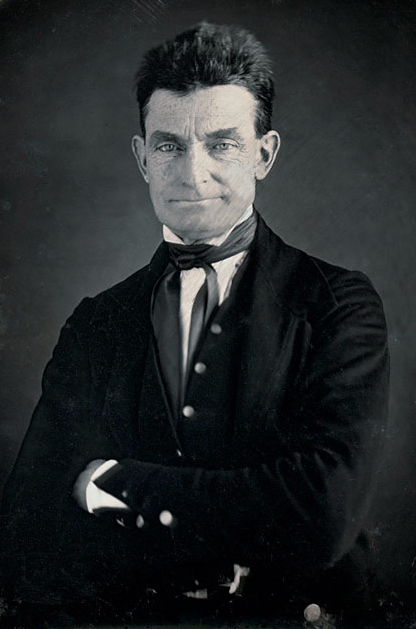

In the home of William Webb, John Brown and Frederick Douglass met several African-American Detroit residents on March 12, 1859, to discuss methods of abolishing American Negro slavery. Although they differed on tactics to be used, they were united in the immortal cause of American Negro freedom. Among the prominent members of Detroit's Negro community reported to have been present were: William Lambert,George DeBaptiste, Dr. Joseph Ferguson, Rev. C. Monroe, Willis Wilson, John Jackson, and William Webb.

This was a unique day in Detroit’s history when two famous abolitionists meet face to face. In that meeting, John Brown discusses his plans of attack on Harpers Ferry to violently attempt to end slavery and Douglass disagreed with the plan because of its violence. This would ultimately be the last time the two meet in person before John’s Brown death after his capture at Harper Ferry, by U.S. Colonel Robert E. Lee.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass, ex-slave and internationally-recognized antislavery orator and writer, sought a solution through political means and orderly democratic processes.

John Brown

John Brown, antislavery leader, ardently advocated insurrectionary procedures, and eight months later became a martyr to the cause.

Dr. Betty Shabazz (1936-1997) Activist & Educator

American Activist, Civil Rights Leader, Educator, and Health Administrator

Betty Shabazz was born Betty Sanders on May 28, 1936, in Detroit, Michigan. Betty was adopted as a baby and raised by Helen and Lorenzo Don Malloy. She was their only child. Betty Shabazz was a private person who didn't reveal much about her early life. Betty grew up in a middle-class family in a thriving Detroit neighborhood filled with black businesses and churches. Her mother was very active in community groups and particularly in their church, Bethel A.M.E. (African Methodist Episcopal). Betty led a very sheltered life that revolved around family, school, and church.

Betty graduated from Northern High School in Detroit in 1952. She then attended Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), a historically African-American college in Alabama that her father had also attended. It was her first experience in the South and her first time away from the protected environment of her parents' home, and she had her first experiences with racism there. At Tuskegee, she planned to major in elementary education, but decided to switch to nursing instead. The dean of nursing suggested that she attend a three-year nursing school, so Betty transferred to the Brooklyn State Hospital School of Nursing in New York. There, she earned her certification as a registered nurse (R.N.).

It was in New York that she met her future husband, the civil rights activist Malcolm X. Betty interrupted her education for several years after they got married and started having children. Years later, after the assassination of her husband, she returned to school. She earned her bachelor's degree (B.A.) in public health education from Jersey City State College. She earned her doctorate (Ph.D.) in education in 1975 from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

The death of Betty Shabazz touched many people, bringing forth an outpouring of sympathy. Despite facing one of our nation's great historical tragedies, Shabazz was determined to raise her daughters, return to graduate school, earn her doctorate, and devote herself to a career. Betty Shabazz became an important symbol of our age, as Frank Bruni explained in the New York Times. "Dr. Shabazz's struggle and violent end became, for many African-Americans, a universal allegory of aspirations, perseverance, bitter disappointments, and uncontrollable twists of fate. For many, Betty Shabazz was an icon of modern black history.

Betty was honored her for her courage, modesty, and dignity in the face of overwhelming adversity. Over and over, people praised her tenacity, fortitude, and perseverance, calling her a symbol of strength and pride. "[The] woman known universally as Sister Betty faced more than her share of trials," according to Ebony magazine, "but she confronted them all, giving America, and black America especially, one of the great images of the indomitable tenacity of the spirit, and especially the indomitable tenacity of spirit of great black women."

LeRoy Foster (1925-1993) Artist

Detroit’s Own Michelangelo

Foster was born in Detroit on May 8, 1925, and lived there his entire life.

Foster began drawing at age five or six, eventually being recognized by teachers and peers as an exceptional art student. In 1939, at age 14, he won first prize at an exhibition of the Pen and Palette Club, a training and studio space for black artists sponsored by the Detroit Urban League. He was the youngest member.

At the Pen and Palette Club, Foster studied with Hungarian artist Francis de Erdely, who was renowned for his skill in figure drawing. Foster went to Cass Technical High School and also studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills. Through the help of his teachers at Cass, he received a scholarship to study at the Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies), where he studied under painter Sarkis Sarkisian. After that, Foster spent time studying in Europe, at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, and the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London.

Foster came to be known around the city as an artist with a mastery of human anatomy, an excellent portrait painter, and, perhaps most widely acknowledged, a public muralist with a commitment to African-American history and culture.

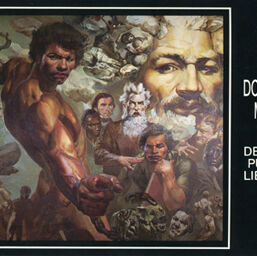

Frederick Douglass mural, Detroit Public Library, 1971

The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Leroy Foster's 10 x 12 foot mural, commissioned by the Afro-American Museum of Detroit is on view at the Detroit Public Library's Frederick Douglass Branch Library in Scripps Park

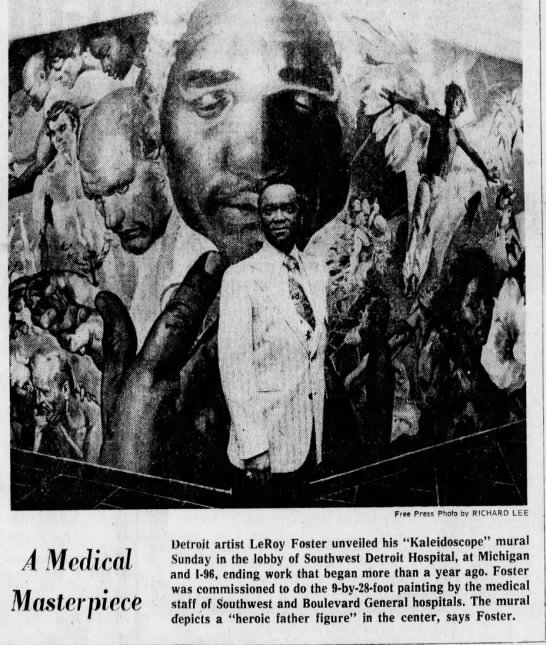

Newspaper clipping of Foster w/ Kaleidoscope, a 9' x 28' mural in the lobby of Southwest Detroit Hospital

Kaleidoscope, a 9' x 28' mural in the lobby of Southwest Detroit Hospital, a commission was a joint venture between the medical staff of Boulevard General Hospital and managers of Southwest Detroit Hospita

Fel'le's "King LeRoy" mural. Photo by Nick Hagen.

Mural of LeRoy on his old Building located at 16561 Livernois, Detroit MI 48221

Marjorie Bradfield (1911-1999) First African American Librarian hired by DPL

Marjorie Bradfield

Bradfield was the first African-American librarian hired at the Detroit Public Library. Bradfield earned a degree from the University of Michigan in 1934 and graduated from the Columbia University School of Library Service in 1935. She married Horace Ferguson Bradfield, a physician, in 1938. She returned to the University of Michigan and received a Master of Library Science degree in 1940.

She worked to improve the library's resources about African Americans, and helped establish the library's Black History collection. In 1967 the Detroit City Council increased funding for minority literature due to her efforts, including money to help expand the library's Azalia Hackley Collection of black literature about the performing arts. In 1968 Bradfield became a librarian of the Detroit Public Schools system, where she established literature programs for Black History Month. In 1980 she retired from Detroit Public Schools.

Focus on Black History

Mrs. Bradfield's obituary in the Detroit Free Press talks about her career, including her pivotal role in establishing collections focused on black history in the Detroit Public LIbrary system.

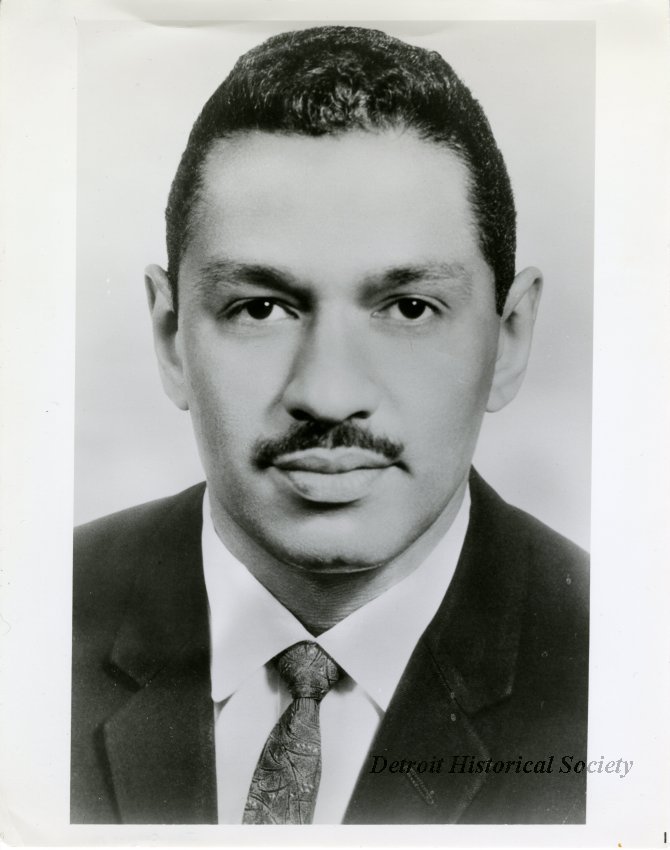

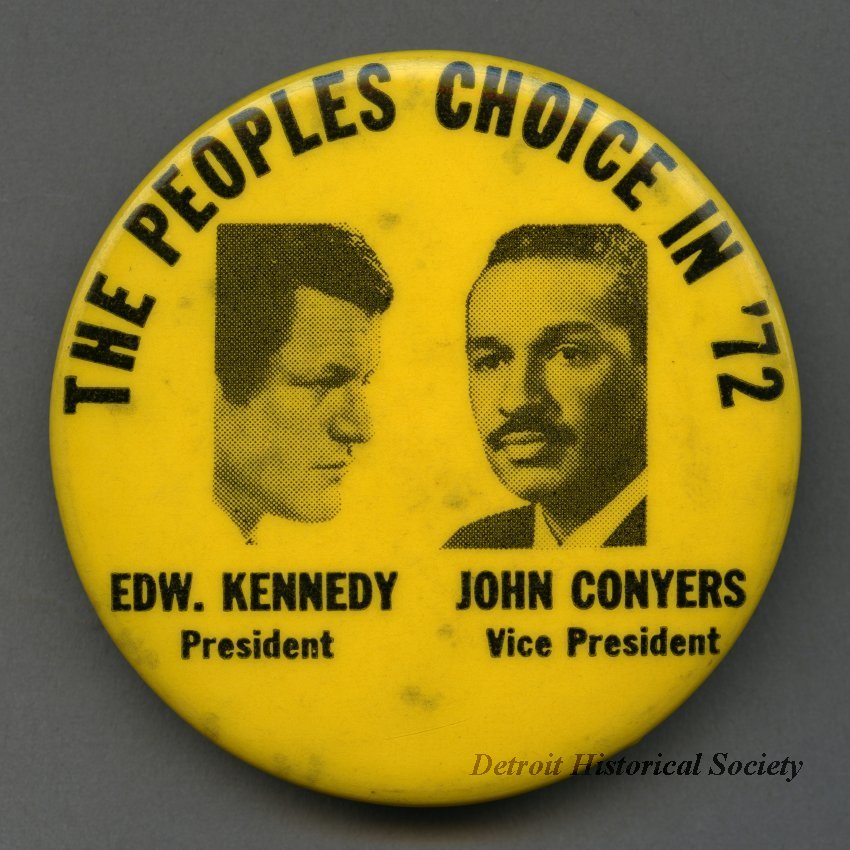

John Conyers (1929-2019) Congressman, U.S. House of Representative

John Conyers Jr.

John Conyers, Jr., born May 16, 1929, was a congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives for 53 years, the longest-serving African American congressman in the U.S., the sixth longest-serving over all. Representing a district that covers parts of Detroit and some adjoining Wayne County suburbs, Conyers was elected to 27 terms in Congress.

Conyers graduated from Northwestern High School and went on serve in the National Guard and the United Stated Army during the Korean War. He later received both his undergraduate and law degrees from Wayne State University.

After working for three years as a legislative assistant for U.S. Representative John Dingell, Conyers himself ran for office, and was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives in 1964. During his time in Congress, Conyers chaired the House Committee on Government Operations and was chairman of the Committee on the Judiciary. Conyers was also one of the 13 original founders of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Image Source: Detroit Historical Society

His time in office

Recognized and heralded as one of Congress’s leading liberals, Conyers was on the executive boards of the American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP from the early 1960s until his death. He sponsored legislation that sought to prevent juvenile offenders from receiving life sentences, and to combat police brutality against African American men, as well as defending the Voting Rights Act and seeking reparations for descendants of African American slaves.

Conyers fought for 20 years to establish a national holiday to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., introducing a bill each session of Congress beginning in 1968. The legislation designating the third Monday in January as the holiday was signed into law in 1983 and went into effect in 1986.

Image Source: Detroit Historical Society

Relationship with Rosa Parks

An integral part of Detroit’s history, Conyers was in the streets, seeking to ease tension during the 1967 civil disturbance, and hired Rosa Parks to work in his Detroit office. He was active throughout his career in the advancement of the Civil Rights and Labor movements. He twice ran for mayor of Detroit, in 1989 against Coleman Young and in 1993 against Dennis Archer.

His Resignation

Challenges to Conyers’ conduct arose twice before the House Ethics Committee, the first in 2003 alleging use of his office for personal means, and in 2017 for paying an ex-staffer for time not worked. But it was allegations of sexual harassment that led Conyers to resign his ranking position on the Judiciary Committee, and eventually resign from Congress, on December 5, 2017.

His father, John Conyer Sr.

Portrait of John Conyers, Sr., father of John Conyers, Jr. He was the chief steward of UAW Chrysler Local 7, a labor union organizer, and international representative of the UAW.

Image Source: Reuther Library

Arthur L. Johnson (1925-2011) NAACP President, WSU Vice President & Faculty

NAACP Portrait

Arthur Johnson was an author, civil rights activist, and former senior vice president of Wayne State University.

Johnson is an Americus, Georgia native, later moving to Detroit in 1950. There, he became the executive secretary of the Detroit chapter of the NAACP. He held that post for 14 years during the tumultuous years of the civil rights struggle.

Johnson served as deputy director of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and assistant director of the Detroit public school system. For 23 years, he served in various administrative posts at Wayne State University in Detroit, before retiring in 1995.

Image Source: Reuther Library

NAACP Officers

Johnson helped stage the first sit-ins at restaurants on Woodward Avenue; helped enlarge the Detroit chapter of the NAACP into one of the nation's largest and most successful chapters; Johnson had served as president of the Detroit branch of the NAACP from 1987 to 1993. Prior to that, the Georgia native was heavily involved with the national civil rights movement. He attended Morehouse College with King and served as executive secretary for the national NAACP.

Image Source: Reuther Library

NAACP, Fight for Freedom Dinner, Sponsorship, 1961

Johnson helped organized the largest sit-down fund-raising dinner in the world, the annual Freedom Fund Dinner which draws 10,000 people and raises more than $1 million each year.

Image Source: Reuther Library

Arthur L. Johnson Collection of African American History at Wayne State University

The Arthur L. Johnson collection of over 200 books, videos and non-print materials which reflect the history of African Americans as it relates to the civil rights movement in the United States. The purpose of the collection is to serve the teaching and research needs of students and faculty, as well as the Detroit metropolitan community. The collection began in 1993 with a donation of several print and non-print materials from Arthur L. Johnson and the establishment of the Arthur L. Johnson Endowment.

Image Source: Reuther Library

Book Recommendation

Arthur L. Johnson's memoir, published by Wayne State University press in 2008.